Reflection

With the activities and excitement from each intervention, the intervention participants began running their own math centers. One student who was excited to be a leader struggled to stay focused and to count in Spanish in the beginning of the year, but our efforts showed a marked difference in his confidence and math fluency.

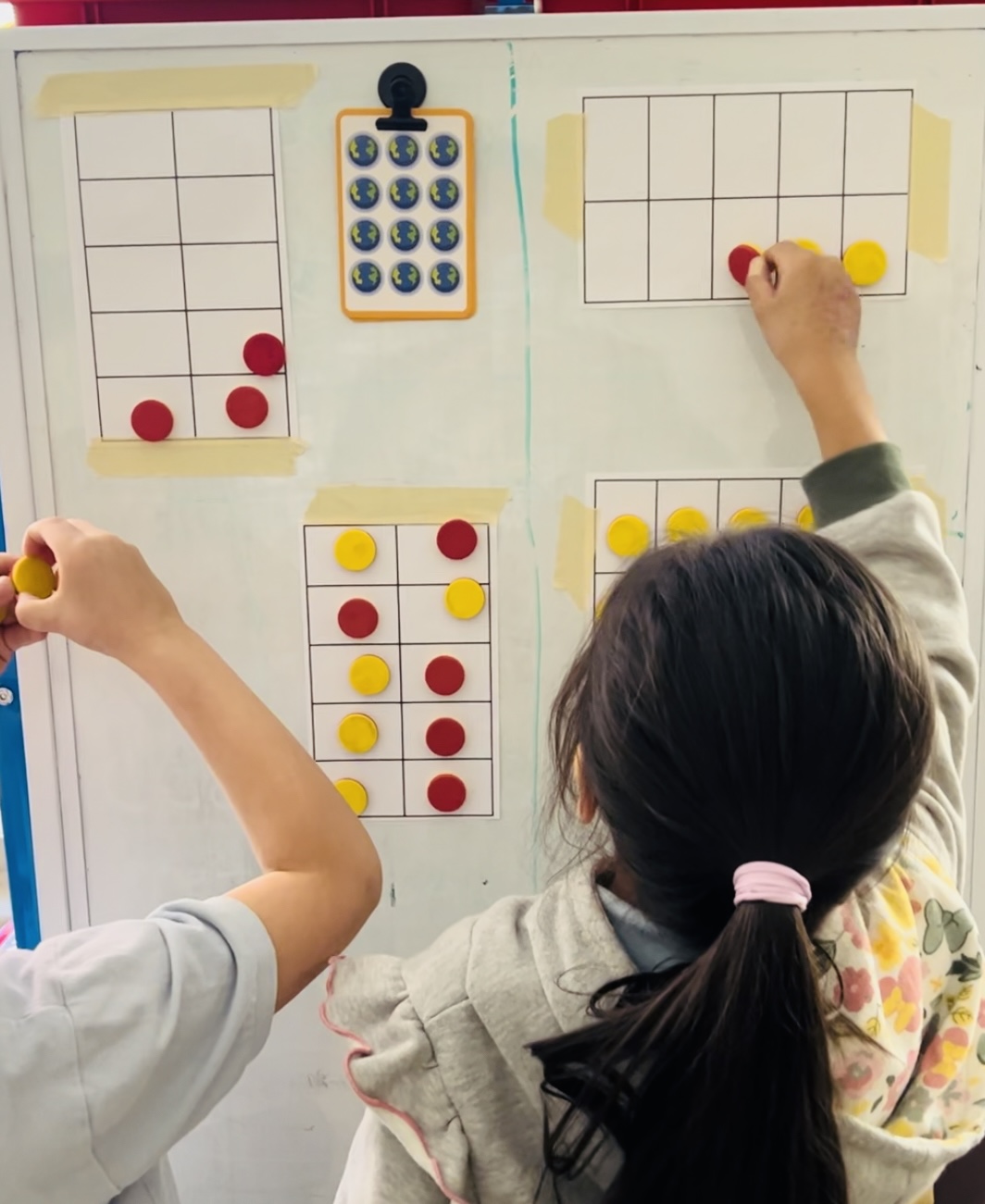

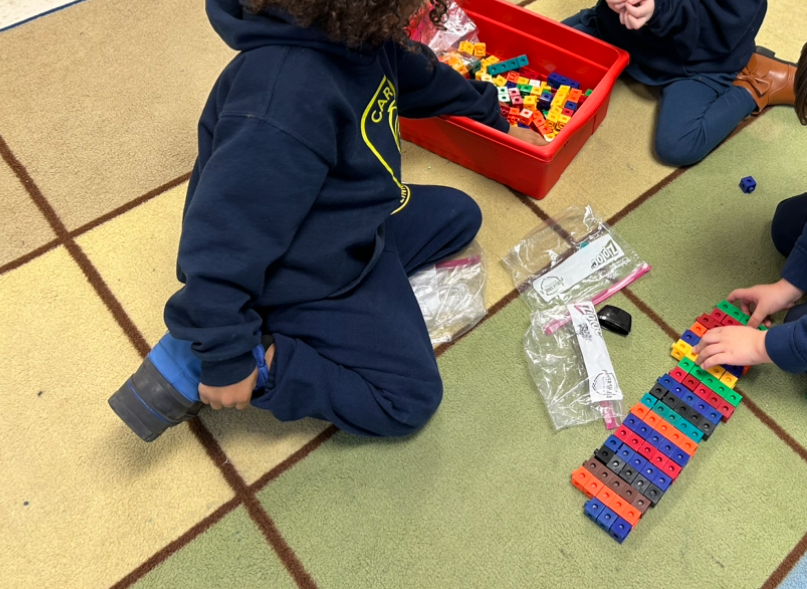

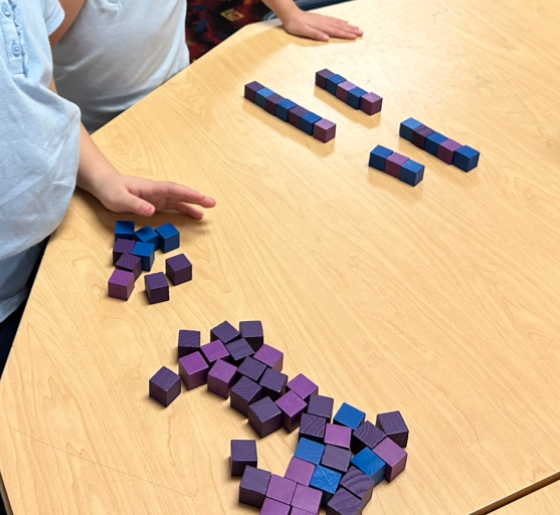

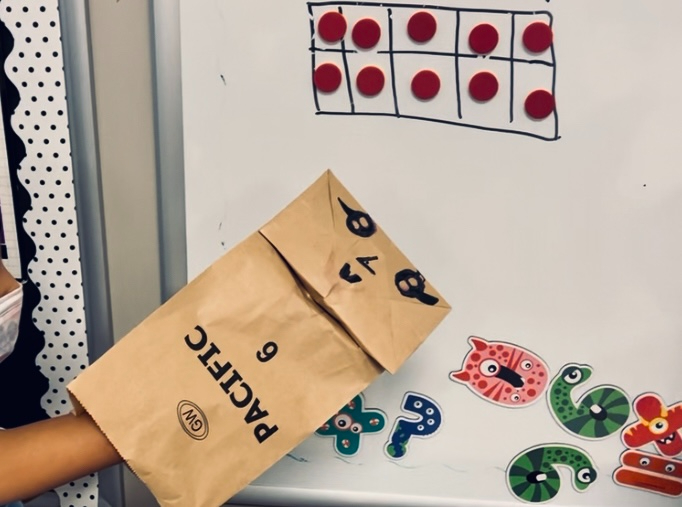

I feel that by opposing the “banking method” of education (Freire, 1970), in which I would have continued using the GoMath templates to prescribe the number formations, I allowed students the space and time for trial and error. It became more experiential and ultimately did require them to know how to make numbers from 0-10. They adjusted to teen numbers and strengthened the base-10 foundation.

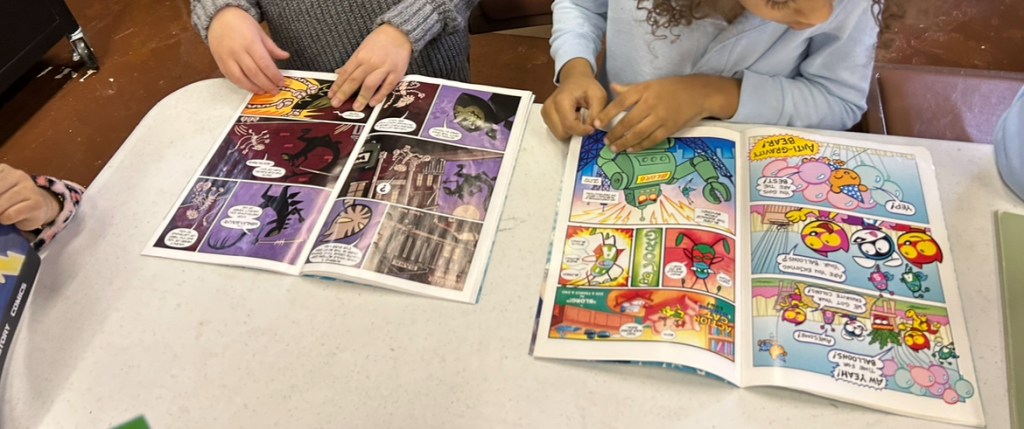

Finally, I believe that for all students, seeing kids their age in the stories reflected more than just possibility. Their realities were changed when they saw Marco, Usha, and Lia and Luis doing something that they could also do. These math tasks became tangible, their authority on the subject matter became credible, and my students have come to absolutely love math. I know that when I started this project, I wanted to make the dual language experience something that was not so scary for 5 and 6 year old kids. Being put in an immersion class with students who have different levels of Spanish fluency, or even the confidence to participate and play, can be a years’ long effort in the classroom.

Originally, the students who joined my class from the shelter were predominantly Afro-Venezuelan. Some students who relocated also changed schools, but three Afro-Venezuelan girls and one Ecuadorian girl remain in the class. They have been participating in my small group exercises once a week since our middle of the year testing cycle ended mid-January. In this group are two other children, one who was the only Black student before they arrived, and the others include monolingual English students. The parents of my Black American student have also asked me about Spanish lessons for themselves because they feel at a disadvantage in terms of at-home practice.

Since that moment in the beginning of the year, I have been working on pulling resources that are accessible to everyone because I empathized with them from my time as an English language learner without access to outside academic English support.

After the conclusion of this project, I noticed what can only be explained as an inadvertent socially elevated position of the participants. Compared to the beginning of the year these students were going first (which is a very big deal in kindergarten), and they became the knowledgeable group. These correlations are highlighted early in the year because students will notice the speed at which someone answers accurately sometimes earns praise.

Finally, I resolved to taking this project on over multiple days in the week, because the timing had to be sensitive to student abilities. Not all students can handle being in the same center for the time necessitated in each session. Ideal conditions for interventions include

- The support of at least one additional staff member to attend to students not in the group.

- Smaller class sizes: as a self-contained teacher involved in every part of the learning process, I believe that class size directly affects the ability of teachers to run small groups while managing the whole classroom.

- The use of storytelling through family events and curriculum nights to better prepare students families for the expectations of dual language kindergarten.

References

Charles Horton Cooley, Human Nature and the Social Order. 1902.

Freire, Paulo, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 1970.

Rosenberg, Marshall, Nonviolent Communication, 1960.

Tatum, Beverly Daniel. Why are all the Black Kids Sitting together in the Cafeteria? And other conversations about race, 1997.